Back Home by Chris Hardie

There were always at least three daily chores that had to be done on the farm – feeding the cows, milking the cows and repairing whatever broke down.

If we were lucky, the latter would be a minor repair, perhaps just a minor adjustment on a stanchion. But those days seemed to be few and far between. Dealing daily with power take-offs, silo unloaders, tractors and lots of moving and mechanical parts meant there was always something breaking down.

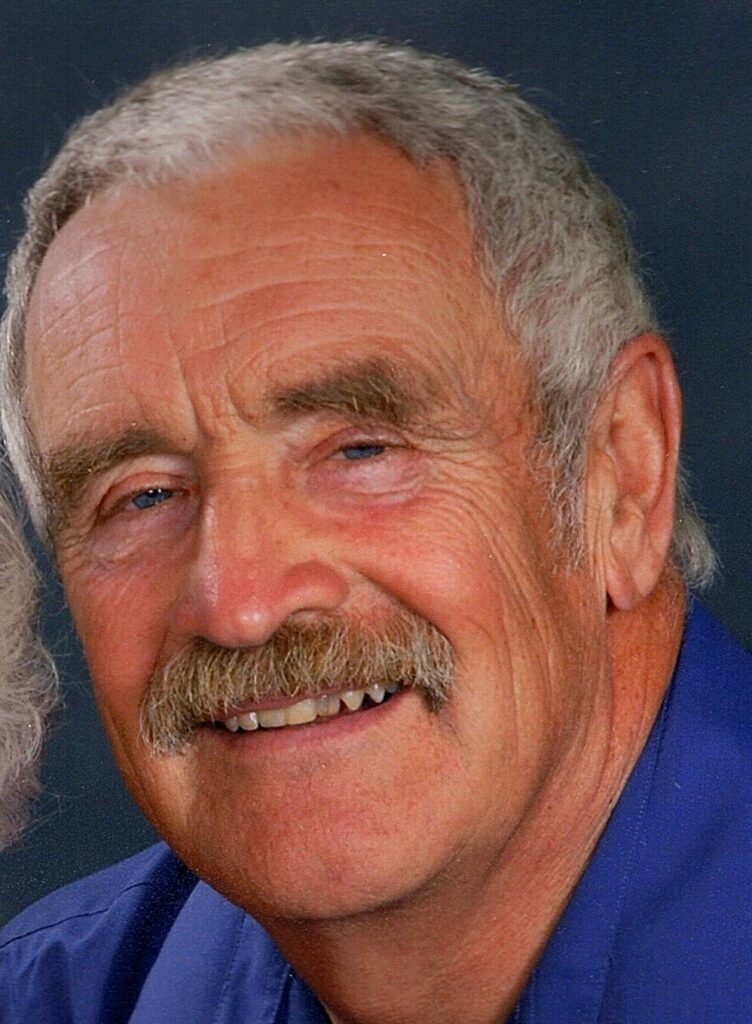

My late father always carried a large pair of pliers that were used to squeeze, cut, bend or pound reluctant bolts, screws, wire and twine. Dad was very skilled at repairs and was a capable welder – one skill I wish that I would have learned.

I remember one bitterly cold morning when the temperatures forced him inside the milkhouse to weld. He was just finishing up when the milk inspector paid a surprise visit.

Welding is not on the list of approved milkhouse activities on a Grade A dairy operation. But the inspector – knowing the challenges of farming in below zero temperatures – just shook his head and came back another day.

Dad’s other tool of choice was a hammer. He was fond of saying that if you couldn’t fix it, you simply needed a bigger hammer.

There is truth to the need for blunt force when you’re trying to break loose rusted metal bolts or seized up bearings or shafts. Blunt force was absolutely necessary, especially during the winter when getting the manure spreader ready. In order to make sure that the chain and the apron were free and not frozen, a heavy iron bar was used to pound on the paddles and chain.

That was the prudent option. The other risky option was to hope the warmer manure would thaw the paddles before you turned on the power take-off. Hearts would sink when you heard the snapping sound of a frozen chain break with a full spreader that could then only be emptied by manual labor.

We had several different sized ball peen hammers and a few sledge hammers. Normally the 12-pound sledge was adequate for the job. But every so often the job called for the nuclear option – Big Bertha.

Big Bertha was a 30-pound cylinder of iron on the end of a walnut handle. She’s long gone, so I have no photo, but picture the same ratio of a can of soup on the end of a pencil. Her edges were a little squashed – the scars from previous battles.

I could scarcely lift Big Bertha when I was very young and had to drag her across the floor. I knew I had become a man when I could actually swing and control her. But with a few swings and the assistance of some colorful metaphors, she usually got the job done.

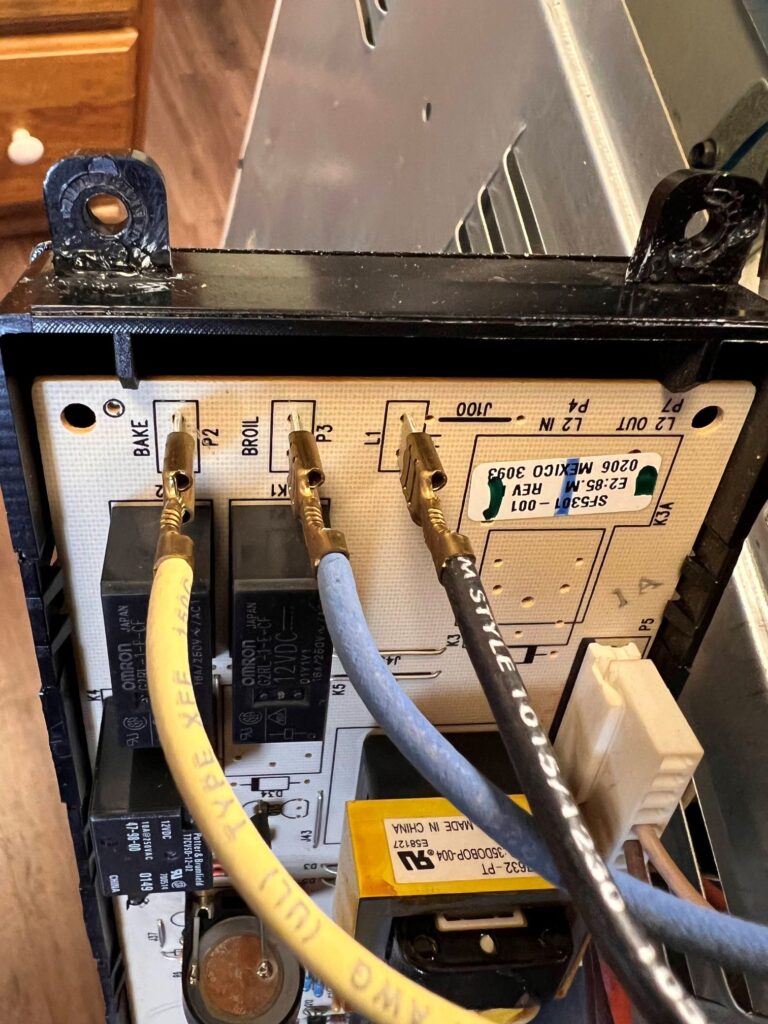

I thought of Dad recently while I was repairing the circuit board on our electric stove. The entire board fell backwards into the top of the stove one day when my wife Sherry was setting the temperature.

When I finally got around to attempting a repair – the oven still worked, afterall so there was no rush – I didn’t need a hammer. This job required a more delicate touch as I discovered that the four plastic clips that held the circuit board in place had broken off. Why plastic was used instead of metal is the eternal question asked by millions engaging in repairs even when we know the answer. (Because it’s cheaper).

I salvaged the clips with the aid of some glue and so far the repair is holding.

I didn’t even have to use any duct tape or twine.

Dad would have been proud – and would have had a hammer ready just in case.

Chris Hardie spent more than 30 years as a reporter, editor