Back Home by Chris Hardie

» Download this column as a Word document

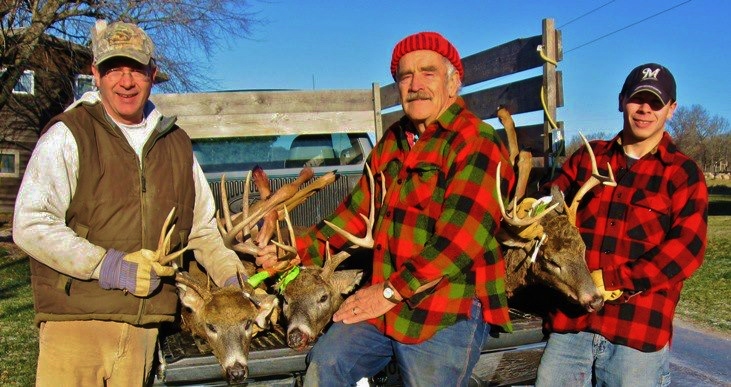

» Download the photos that accompany this story

» Chris Hardie’s headshot

Dad sipped coffee poured from his dented thermos as we watched a large gray squirrel scamper up a nearby tree.

We were sitting in a deer stand overlooking two fields. It was late morning Nov. 23, 2019 — the opening day of the Wisconsin gun-deer-hunting season. It was the 70th season Dad was participating in the annual hunt. We knew it was going to be his last.

Dad’s mobility and mental alertness had been declining for several years. The previous year, he sat with me in my hunting stand for a few hours and had difficulty climbing the hill. We were concerned about his safety.

Dad was an expert hunter. He knew the farm like the back of his hand. He never built a deer stand but always sat in the same valley where deer frequently crossed. As the landscape changed, he would move his spot. But he always got a deer — and it was usually the biggest buck taken that year from the farm. In 1983, he shot an 8-point buck with a 21-inch spread that field-dressed 200 pounds.

During the past four or five years, Dad hadn’t gotten a deer. He never even took a shot. But it was still important for him to be in the woods — especially on opening day.

When Dad announced that he was going to hunt, my son, Ross, and I built a deer stand that was easily accessible from a field road. It wasn’t an ideal location, but through the years it has been a spot where deer have been taken.

We didn’t want him hunting alone so we agreed to take turns. Ross started the morning by driving Dad to the stand and sitting with him for the first few hours. I came over in the late morning.

“What kind of tree is that?” Dad asked, pointing to a nearby gnarly burr oak.

Dad once did a 4-H project where he created a display of all the different trees found on the farm. He knew trees.

But not today.

“I think that’s a burr oak,” I replied.

“Oh sure,” he nodded in agreement.

The fields we overlooked were cleared by my great-grandfather. Dad had told me the story many times. I wanted to hear it again.

“Weren’t these fields cleared by Grandpa Ray?” I asked.

“Yes they were,” he said. “They used a stump puller and dragged the stumps out with a stone boat. Can you imagine how hard that had to be?”

Old memories came out easily most days. We talked about his first hunting experiences on the public land on the eastern side of Jackson County because deer were then scarce on our farm. We talked about his father and how he always hunted over an open fire — a tradition I carry on.

For a few moments, it was like the old days — a father and son sitting together in the cold November woods, sharing a bond that transcends simply pulling the trigger of a gun.

Like the second day of the 1978 season when Dad insisted I hunt from his stand; I shot my first buck. I was just finishing the field dressing when Dad walked down the hill.

“You got one,” he said in his matter-of-fact style.

“It’s not that big,” I replied, mentally comparing the single antlers to the 8-pointer he had shot the previous morning.

“No, it’s a nice one,” he said with a smile.

A load was lifted from my shoulders. I was no longer the buck-fever kid who couldn’t shoot. As I stood there with my father, a little less than a month removed from my 15th birthday, I felt like a man. It wasn’t the thrill of the kill but the sense that I belonged.

Like the first year Ross shot a deer and excitedly came to Dad to share the news.

“Grandpa,” he said. “I think I shot a deer.”

“Well, we better take a look,” Dad replied.

Like the morning of the blizzard of 1991 when 13 inches of snow fell on opening day. I shot a doe at about 10 a.m. and had started a fire to stay warm. Dad came down the hill behind my deer stand dragging a log to throw on my fire.

Like the year Dad couldn’t find his license but went hunting anyway before his duplicate was in hand.

“No jury in Jackson County is going to convict a man for hunting on his own land,” he harrumphed as he headed out the door.

Like the year when he discovered opening morning that Mom had packed his wool hunting clothes in mothballs — not a scent that blends in with the woods.

So many memories.

So many stories.

Dad fell silent.

“What kind of tree is that?” he asked, pointing to the same tree we had discussed 20 minutes before.

“I think it’s a burr oak, Dad,” I said, turning my face away to wipe my moistening eyes.

“Oh sure,” he said.

A little while later, Dad said he wanted to watch the Wisconsin Badgers football game. I gave him a ride in the truck and he settled into his easy chair. Dad’s last hunting season had ended.

Dad always said when it was his time to go he wanted it to be in the woods under his favorite tree. He didn’t exactly have his wish, but he did die at home.

My 45th hunting season this year will be sad because my hunting partner and mentor is gone. The woods will seem empty.

But Dad will be there nevertheless.

Because his memories and stories remain.

Chris Hardie spent more than 30 years as a reporter, editor