By Chelsea Hylton, Francisco Velazquez and Dee J. Hall, Wisconsin Watch

Tamia Fowlkes of Milwaukee was among thousands of voters in Wisconsin who reluctantly went to the polls on April 7. Fowlkes had voted absentee — like more than a million other voters in the state — but then helped her grandfather cast his ballot in person after the state Supreme Court ruled that Gov. Tony Evers lacked the authority to delay the election because of the pandemic.

“We were the only state in the entire country to have an (in-person) April primary,” said Fowlkes, a University of Wisconsin-Madison student active in registering students to vote. “I don’t know if there was any way to make it safe, because it just wasn’t something that we should have been doing.”

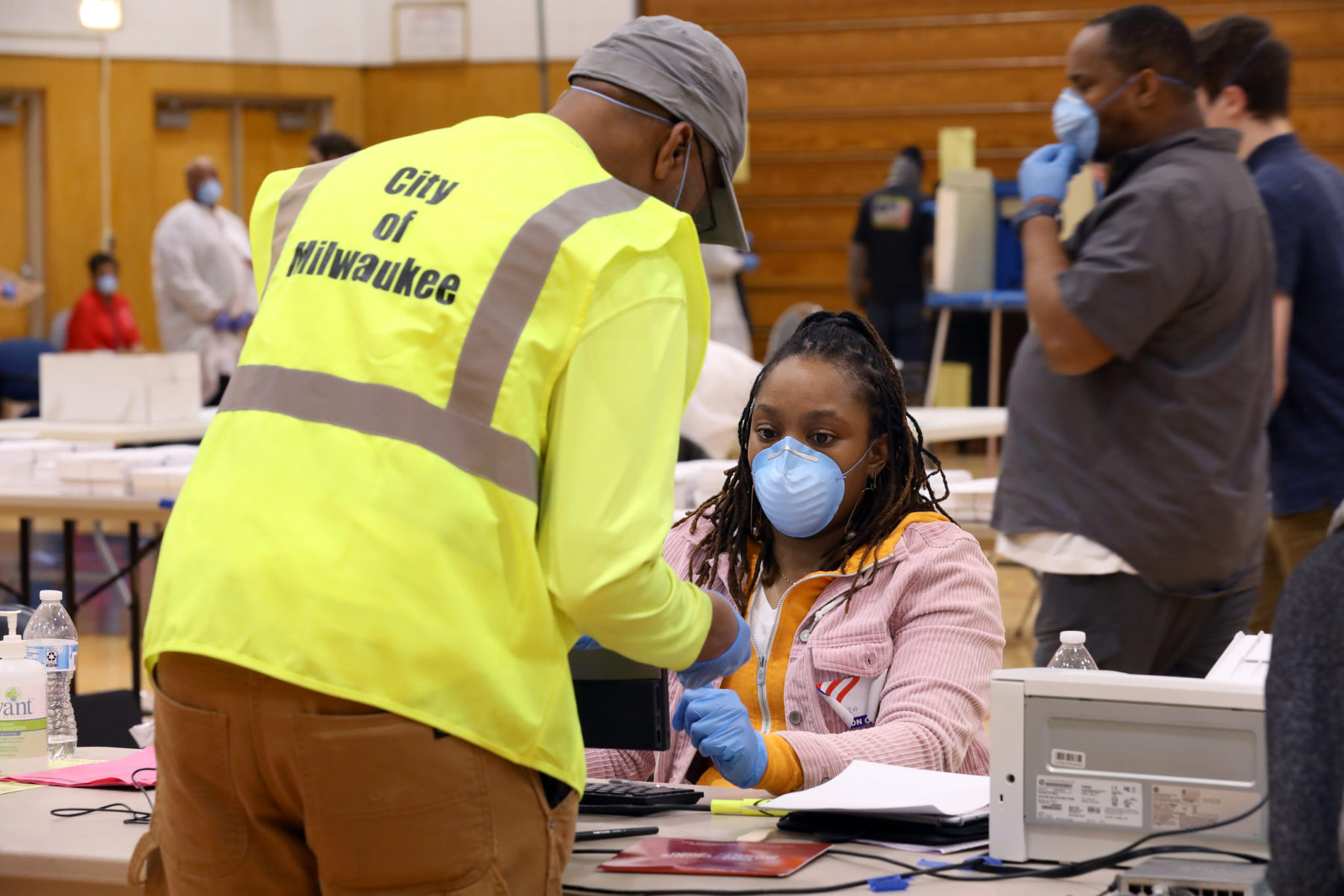

Last week, state officials said as many as 52 people — including National Guard members, voters and poll workers — developed COVID-19 after in-person voting, although it is possible they were exposed in other ways. That day, voters chose former Vice President Joe Biden as the state’s Democratic selection for president and liberal judge Jill Karofsky to join the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

- Download this story as a Word document

- Download the photos that accompany this story

- View the original story on WisconsinWatch.org

On May 12, voters in central and northern Wisconsin will again be asked to cast ballots during a pandemic, this time to replace U.S. Rep. Sean Duffy in the sprawling 7th Congressional District. Wisconsin also has an Aug. 11 partisan primary and the Nov. 3 general election, which will decide Wisconsin’s pick for president and races for Congress, Legislature and district attorney.

As the presidential election and a possible bigger wave of the pandemic could collide this fall, a top civil rights advocate told reporters last week that Wisconsin’s April 7 election was “a wake-up call” for the nation.

“What happened in Wisconsin was a travesty that put voters in the crosshairs of having to choose between their safety and their vote,” said Vanita Gupta, president of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights and a member of the “cross-partisan” National Task Force on Election Crises, which pushes for a “free and fair” 2020 election.

“The choices that we’re making now are going to determine not just how we weather the storm of this virus, but also the kind of democracy we’re going to have when it’s over.”

A poll commissioned by the liberal electioneering group A Better Wisconsin Together found that half of Wisconsin survey respondents who did not vote April 7 cited coronavirus concerns as a reason. The poll of 1,288 likely November voters was taken April 11-14.

Gupta is working with a large coalition of advocacy organizations urging Congress to approve $3.6 billion to help states pay for the extra cost of holding elections during the pandemic.

“Your life is the highest poll tax that anyone’s ever had to pay in order to exercise their franchise,” U.S. Rep. Gwen Moore, D-Milwaukee, said in the call with reporters last week. “The ultimate in voter suppression is to prevent people from exercising their right to vote without showing up in person.”

At least 24 states that had originally planned to hold in-person elections in April and beyond have postponed, cancelled or converted them to all mail-in voting. During this time, Wisconsin’s Republican legislative leaders have stood firm: The elections will go on.

But many questions loom: Will there be enough poll workers? Will voters again risk exposure to COVID-19 with in-person voting? Or will Wisconsin’s absentee ballot system — which frayed under a record 1.28 million requested ballots for the April 7 vote — be able to handle the surge?

Diane Coenen is the city clerk for Oconomowoc and president of the Wisconsin Municipal Clerks Association, whose members run Wisconsin’s elections. Coenen worries about the May 12 election as well as the elections to come later in 2020.

More clerks than normal have either retired or quit in recent weeks, she said — an unusual step during a presidential election year. The Wisconsin Elections Commission says 244 National Guard troops will work at polling sites on May 12, and truckloads of sanitizer, gloves and masks went out to the counties in the 7th District last week. Evers’ Safer at Home order is in effect until May 26.

“As long as this coronavirus threat is out there, you’re going to have employees who are not comfortable dealing with the public — and you can’t force them,” Coenen said.

Because of the pandemic, just three of the 15 sworn poll workers are willing to work the May 12 election in Thorp, a city of 1,800 in Clark County, Wis., said Marie Karaba, an administrative assistant for the city. Karaba said voter turnout is “absolutely depressed because of this pandemic and also due to this being the only contest on the ballot.”

Said Coenen: “Those clerks, staff, volunteers, poll workers that are manning the polls — they’re going to be at risk twice. That’s pretty heart-wrenching, when you think about it. We are doing our jobs, but we have never faced these types of circumstances.”

Is mail-in voting the answer?

Coenen is recommending that municipal clerks encourage voters to cast absentee ballots to reduce the risks inherent in in-person voting. But without more help — financially and otherwise — clerks in upcoming elections may not be able to manage the “avalanche” of absentee ballots, she said.

An investigation by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, the PBS series FRONTLINE and Columbia Journalism Investigations found widespread failures in absentee balloting on April 7, including ballots requested but never received, empty envelopes containing no ballots and multiple ballots sent to the same person.

The U.S. Postal Service — which is struggling under the weight of the pandemic — also is investigating why scores of absentee ballots in eastern Wisconsin were sent to the post office but never delivered to voters.

In Coenen’s Waukesha County city, Oconomowoc, 15% of people voted absentee in 2016. In April, that surged to about 85%, she said.

Processing that amount of absentee balloting “is just not anything we’re prepared for,” Coenen said. “We can’t do this every election. It’s just unrealistic.”

In the April election, nearly 4,700 absentee ballots were rejected because they were received by election officials after the April 13 deadline, according to Wisconsin Elections Commission statistics cited in a federal court filing last week by Democrats. And nearly 12,000 absentee ballots that were received were rejected for having insufficient witness certifications — a requirement that was imposed, waived and then reimposed during a last-minute court battle.

Citing the pandemic, the state and national Democratic parties are asking that Wisconsin be temporarily required to extend deadlines and loosen requirements for absentee ballots and registration.

The defendants — the Elections Commission, the state and national Republican parties and the state Legislature — have asked the U.S. District Court in Madison to dismiss the case as “moot,” arguing that the April 7 election the lawsuit originally sought to delay is now over.

University of Wisconsin-Madison student Synovia Knox was among the many Wisconsin voters who tried but was unable to vote by mail last month. Knox said she requested an absentee ballot that did not arrive in time.

“My biggest concern was the spread of germs,” Knox said. “My absentee ballot didn’t show up until the day after voting took place, so I felt like I had no choice.”

She cast her ballot at Madison’s Catholic Multicultural Center, where voters mingled with a long line of people waiting to shop at the food pantry.

Long lines, tension at polls

Wisconsin’s election system, the most decentralized in the country, features a unique trait: The state offers guidelines and support for elections, but it is up to the state’s 1,850 municipal clerks and 72 county clerks to administer them.

That duty carried new weight on April 7 as clerks scrambled to figure out the best way to make voting safe.

Across Wisconsin, clerks erected plexiglass barriers to separate poll workers from voters. They handed out gloves and masks to workers and provided hand sanitizer to everyone. Many offered curbside voting.

In Milwaukee — which reduced its polling places from 180 to five because of a lack of staff willing to work the election — lines stretched for blocks, causing hours-long waits.

Fowlkes, the UW-Madison student, described the atmosphere at the Milwaukee polling place she visited as tense, as some people did not honor social distancing.

“People would walk past you on the sidewalk, and you could see people kind of like shifting out of the way or trying to move,” she said.

Fowlkes said some of the safety measures made voting more difficult. Milwaukee allowed voters to remain in their vehicles for curbside voting. But the lines of cars became unwieldy.

“There are people who did that and didn’t actually get to vote until like 10 or 11 p.m. that night,” she said. “So even though that option was offered, it wasn’t as effective as it could have been.”

Special election next

The next test of voting during a pandemic will come on May 12, when voters cast ballots in the 7th Congressional District, which sprawls across 26 counties in central and northern Wisconsin. The special election will fill a vacancy left by the resignation of U.S. Rep. Sean Duffy, R-Hayward. The race pits state Sen. Tom Tiffany, R-Minoqua, against Wausau School Board member Tricia Zunker, a Democrat who serves on the Ho-Chunk Nation Supreme Court.

Superior City Clerk Terri Kalan said the city was “slammed” in April by the volume of absentee ballots and lack of poll workers. “We were picking people from wherever we could,” she said.

This time around, “I think everybody’s stir crazy and everybody wants to work now,” Kalan said.

But like many clerks, she is urging Superior residents to avoid in-person voting for the rest of 2020.

“I just really hope people take advantage of that (absentee voting) so people don’t have to stand in line,” Kalan said, adding, “Who knows what conditions will be like in November?”

Chelsea Hylton, Francisco Velazquez and Dee J. Hall reported this story, which was produced as part of an investigative reporting class at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication under the direction of Hall. Wisconsin Watch’s collaborations with journalism students are funded in part by the Ira and Ineva Reilly Baldwin Wisconsin Idea Endowment at UW-Madison.