Back Home by Chris Hardie

The recent announcement from the U.S. Department of Agriculture that it will soon require nationwide testing of milk to address bird flu outbreaks in dairy herds took me back many years on the farm.

Once a month – as I recall – we were visited by the Dairy Herd Improvement Association milk tester. The milk tester would show up with a wooden crate with small bottles and collect a milk sample from each cow.

Back in the 1970s and until 1986 when my father installed a pipeline milk system, we milked with buckets that were dumped into the Step-Saver, a stainless steel cart wrapped in hose that was wheeled down the center of the barn aisle.

A foot pedal opened the lid and the milk was dumped into the cart, sucked through the hose and fed into the bulk tank through a glass receiver jar in the milkhouse. The hose was hung from the ceiling by hooks.

In those days, the milk was dumped from the milker machine into a stainless steel pail. The milk tester would move the pail to a hook-hung scale to get a weight, collect a sample in a jar, label it and then dump the milk into the Step-Saver. The milk was weighed by a meter when the pipeline was installed.

The tests were always done over two consecutive milkings – usually evening and morning. I remember we had various milk testers who would stay overnight with us, enjoying my mother’s excellent cooking. I don’t know if the hosting was a requirement or perhaps it was a way to get a discount on the testing price.

The testers came on short notice, but whenever we knew they were coming, Dad would make sure the cows received a little extra protein to see if that would bump up the production.

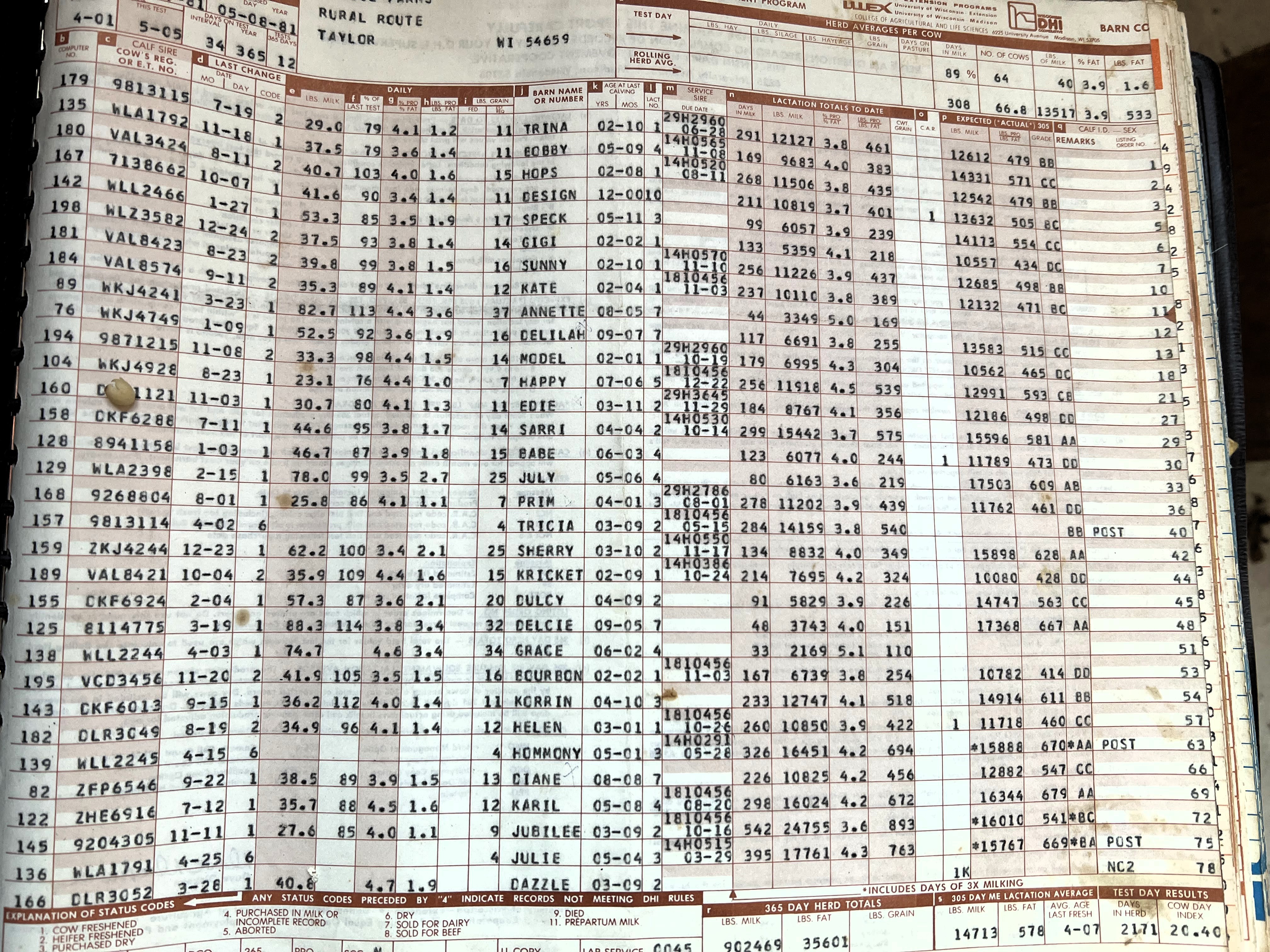

The test reports were compiled in a data sheet that was mailed to the farmer and included milk weights, percent fat, days in lactation and other information.

The start of dairy herd improvement programs can be attributed to University of Wisconsin professor Stephen M. Babcock, who in 1890 perfected the butterfat milk test that bears his name.

Before Babcock, farmers were paid by milk quantity, not quality. Some farmers would even water down their milk to try to get more money.

With the Babcock test, it was possible to start testing for standards and set prices on quality. It was the start of the dairy herd improvement.

The first DHIA was established in 1905 by Helmer Rabild, a Danish immigrant who worked for the Michigan Department of Agriculture. He was hired by the USDA to administer DHIA’s across the country.

Dairy herd improvement also grew with the introduction of artificial insemination in the 1930s when the data would show which bulls sired the highest-producing cows.

Today’s testing is much more advanced than what was available to my parents, including somatic cell count or even pregnancy testing. Today’s milk testers I’m sure cover huge territories as the number of herds has shrunk considerably in Wisconsin.

I discarded stacks of old DHIA test sheets when Dad passed, and Mom moved away. My parents used those test sheets as the building block to improve their herd.

I did save one DHIA test sheet from 1981 just for memory’s sake.

Reading the names of those cows took me back more than 40 years. I remembered some of the names and even where in the stanchion barn they stood. Each cow had its own stall and didn’t like being forced to stand anywhere else.

I didn’t like milking cows as a kid, but didn’t mind it so much as I got older. Time has softened my harsh recollections and today they are fond memories of a long-gone era.

Chris Hardie spent more than 30 years as a reporter, editor