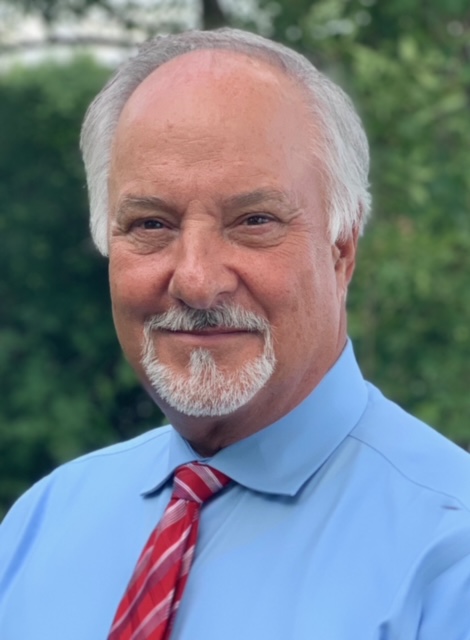

By Bill Barth

My father is dead.

Six strong young Barth men carried him to his grave. He rests beside my mother, who has been waiting eight years. They lie together on the wind-swept Illinois prairie, overlooking now barren fields that in a few weeks will bloom green with the crops that feed America and the world.

Ray Barth lived within a few miles of the Edgar County house in which he was born 95 years, 11 months and 21 days earlier. He survived a serious stroke 12 years ago and, despite long odds, recovered to walk and drive and continue living independently after the passing of his wife of 67 years. His final journey began in early November, when he fell and couldn’t get up. He repeated that he felt regret for being unable to vote. Dad considered democracy a personal privilege and responsibility.

Time broke his body. Never his uniquely American spirit.

As a boy he watched his elders work the ground with teams of horses. He remembered the purchase of the first tractor to be used on the family farm. The Great Depression ruined many farmers, and he told of the emotional wreckage when relatives lost their ground. Dad spoke the names of two young men from the family who died too soon, as warriors for freedom in World War II. He remembered his father’s worry that, at the end of the war, the Great Depression would begin anew. Instead, America’s pent-up energy launched a victorious nation into an economic boom and superpower status. Into that environment, Dad became an adult and rented his own farmland. Soon came a wife and, in relatively short order, a girl and a boy. Country kids, learning life – literally – from the ground up.

Ours has been a family of storytellers, and some stand out. The great-grandmother, recalling childhood in the 1880s, when the prairie grass was taller than a horse’s head. As a mother she lost a 17-year-old son during the pandemic of 1918. She said for months after, she walked the farm for hours alone, the only way she survived the loss. A grandmother – in ways left over from a southern culture, we called her mamaw – who told of selling the entire year’s corn crop for $500 at the height of the Great Depression, instilling fear of failure she never got over. A grandfather – he was our papaw – who recalled being asked by some shady characters to drive a truckload of unknown origin to the south side of Chicago for serious money during the Depression, a request he turned down because it didn’t seem right.

Such values played a central role in the upbringing of children. That world was relatively black and white. There was right, and there was wrong. Deviating from the cultural norm carried consequences.

The timing of things saddled Dad and Mom with the burden of raising two Baby Boomers, both of whom went off to college and built careers away from the farm which had sustained the family since the mid-1800s. Dad sometimes told me he thought my generation had ruined the world. We disagreed on that point. I fully acknowledge my generation broke the old world in many ways. Some of it needed breaking, to allow women to step out of men’s shadow to embrace their own dreams. To join in solidarity with minority Americans no longer willing to be defined by the majority. To challenge government leaders who lied. To question why young Americans had to die on the other side of the world to save face for domestic politicians.

Sometimes, my convictions made conversations difficult on visits to the farm. No doubt, Dad occasionally thought it a direct challenge to the way I was brought up. Becoming a journalist didn’t help. I remember him telling me, during the Watergate affair, about being around a few farmer friends when one cursed reporters and said, “They ought to be lined up against a wall and shot.” Dad said he replied, “Well, I might agree if my son hadn’t become one.”

Differences of opinion, yes. A loss of love, never.

I hope the next generation, and the one following, find ways to bridge the divisions that stem in considerable measure from the cultural earthquake mine created. That’s not an apology for breaking things that needed to be broken. It’s a prayer for healing and acceptance, for realizing the ties that bind us far outweigh the differences that separate us.

As the cycle of life moves on – and I find myself now among the family elders – I look back at my father with admiration and awe for the near-century he experienced. He attended a one-room country school through the eighth grade. He graduated from high school as part of a five-student senior class. During his life Lindbergh flew the Atlantic, the nuclear age dawned, jet contrails crisscrossed the sky, a man stepped onto the moon, and computers took over our lives. Through his own hard work, Dad acquired what mattered to him – substantial land holdings.

Through it all, Dad was the constant for our family. A man somewhat out of time, standing like an oak for us all to gather around and hear stories about how things used to be.

Come spring, we will back his pickup into a field and load it with Barth ground. When Mom passed, Dad insisted on covering her grave with the good black dirt they owned, because the grass just wouldn’t grow well enough with what was there. Family will gather and we will do the same for him.

Bill Barth is the former Editor of the Beloit Daily News, and a member of the Wisconsin Newspaper Hall of Fame. Write to him at bbarth@beloitdailynews.com.