This story was produced by Wisconsin Watch, a nonprofit, nonpartisan investigative reporting organization that focuses on government integrity and quality of life issues in Wisconsin.

- Download this story as a Word document

- Download the photo that accompanies this story

- View the original story at WisconsinWatch.org

by Jack Kelly / Wisconsin Watch and WPR, WisconsinWatch.org

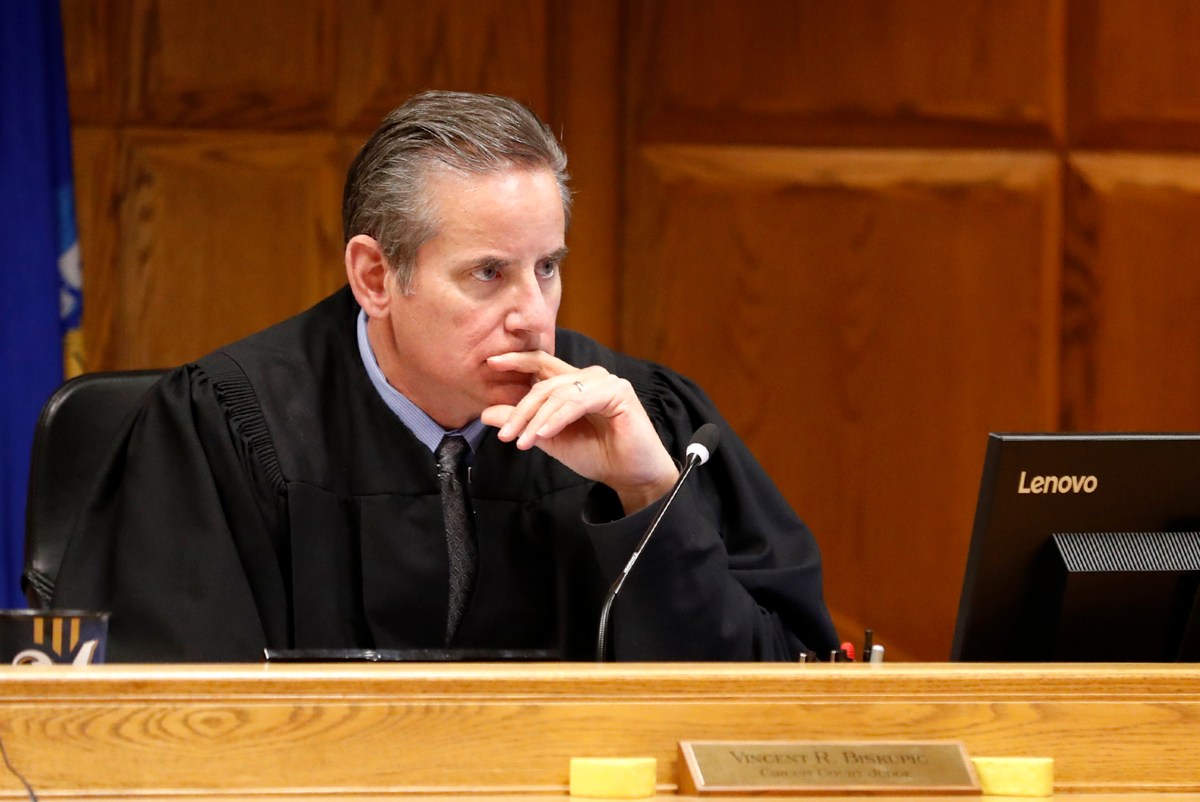

The defendant in Outagamie County Circuit Judge Vincent Biskupic’s courtroom had been sentenced to pay $3,125 in restitution and other court costs for battery and disorderly conduct. Over 11 hearings spanning nearly four years, Biskupic pushed the woman to pay up, at one point ordering her to apply to 20 jobs in a two-week time span to prove she was working toward paying off the debt.

The effort didn’t work. Biskupic eventually held her in contempt for failure to pay and inadequate job searching and ordered 30 additional days in jail if she failed to make overdue payments, court records show. Wisconsin Watch and WPR are not naming the woman because she was not available for an interview.

Over the past seven years, in at least 52 cases involving 46 defendants, Biskupic has used “review hearings” to either monitor a defendant’s behavior or to pressure them to pay court-ordered financial obligations, a Wisconsin Watch and WPR analysis of court records found.

In 23 of those cases, court records indicate that Biskupic monitored defendants’ payment progress. The judge held more than 73 post-sentencing review hearings across those cases, calling a defendant back an average of three times per case. Between 2018 and 2020, Biskupic had four people arrested for failure to show up for review hearings related to their unpaid financial obligations, according to court records.

These practices, which experts say may be legal, are a departure from the norm — and seen by some, even in Outagamie County, as a poor use of resources. And the chief judges who lead Wisconsin’s circuit court system have warned all judges that jailing poor people for failure to pay court-ordered financial obligations could violate their constitutional rights.

In one case, court records show Biskupic held two review hearings to pressure a defendant to pay $516 in court fees and fines for driving after license revocation. The person was arrested in January 2020 for failure to show up at a hearing.

In another driving-after-revocation case, Biskupic held review hearings with a defendant who owed the court $579, ordering the man’s arrest in July 2016 after he failed to show up for one of those hearings. The defendant wasn’t arrested for failure to show until July 2019, almost three full years later, court records show.

In another case in which a defendant was charged with resisting or obstructing an officer, court records show, Biskupic held 10 hearings with a defendant to monitor his progress on paying $4,319 in restitution and other court-ordered financial obligations. Biskupic ultimately tracked the defendant’s payments for nearly three and a half years.

In extensive correspondence, Daniel T. Flaherty, a private attorney with Godfrey and Kahn who represents Biskupic, referenced state statutes and case law he argued gave the judge the authority to monitor the payment progress of defendants. However, some legal experts consulted by Wisconsin Watch and WPR reached other conclusions.

Judge John Hyland of Dane County Circuit Court wrote in a statement that he “did not find such a passage” in the restitution statute — which Flaherty cited — that would allow continued review hearings aimed at monitoring payment. Hyland helped write the Criminal and Traffic Benchbook, the official how-to for Wisconsin judges overseeing criminal cases.

In response to a second statute cited by Flaherty, related to failure to pay fines, fees, surcharges or court costs, Cecelia Klingele, a University of Wisconsin-Madison Law School professor, said “a judge can decide to impose a jail sentence until the money is paid.” She also noted that, “implicit in that power is some ability to monitor whether the money is paid or the work is done, though the statute does not spell out what such monitoring might look like.”

The Wisconsin Supreme Court confirmed in 1972 that it is legal for judges to order defendants to jail for up to six months for failure to pay court costs, fines and fees — which are separate from restitution to victims.

But, said the court, “It must be remembered that courts generally … are not collection agencies and should not be made such.” The decision goes on to say that judges should not imprison indigent defendants with no ability to pay.

“The constitution we believe forbids the imprisonment as a fine-collection method when the court knows it cannot work,” the high court found.

Biskupic declined interview requests to discuss his supervision of defendants, and in a written statement did not explain his motivations for monitoring their progress on court-ordered financial obligations.

Judges rarely collect debts

Civil authorities typically handle debt collection in Wisconsin. Those include the county clerk of courts and the state Department of Revenue, which have no power to issue arrest warrants. Experts involved in the collection of court-ordered financial obligations in Wisconsin counties say judges rarely help collect payments.

A survey sent to all 72 clerks of circuit court by the Wisconsin Clerks of Circuit Court Association on behalf of Wisconsin Watch and WPR also revealed that judges across Wisconsin rarely monitor the status of payments.

Among the 40 clerks who responded to the survey, 34 said judges in their counties do not hold review hearings with defendants who have failed to pay their court-ordered financial obligations.

And even in the six counties where clerks indicated such hearings do happen, the clerks called the practice uncommon. For example, Door County Clerk of Circuit Court Connie DeFere said such hearings “seldom” occur because “we find (the state debt collection program) the BEST for collection efforts.”

Outagamie County is among those that rely on the state revenue department to collect debt, and has been since 2019, according to Curt Nysted, financial operations manager for the Outagamie County clerk of courts office. The county previously referred past due court-ordered payments for tax refund intercept — the withholding of part or all of a defendant’s refund to cover debts owed to the government.

In a phone interview, Nysted said Outagamie courts “have found it more effective” to refer past-due payments to civil authorities and collection agencies than to call defendants back to court to monitor the status of their payments, which he called “not a cost-effective method” to collect past-due payments.

No jailing for debt in ‘decades’

Carlo Esqueda, the clerk of Dane County Circuit Court, told Wisconsin Watch and WPR that if a defendant fails to set up a payment plan and the court-ordered payment deadline arrives, his office issues two letters “asking that the amount be paid, or that a payment plan be arranged.” If they are ignored, they will enter a civil judgment on the case, he said.

From there, the debt is referred to a third-party collections agency. In most Wisconsin counties, that is the state Department of Revenue. At this point, Esqueda said, the debt is no longer the purview of the court or clerk’s office and is handled wholly by revenue officials.

“In Dane County, judges are not involved at this latter stage of the process,” Esqueda wrote in an email, adding “Dane County hasn’t issued a warrant/put anyone in jail for nonpayment of court-ordered financial obligations in decades.”

La Crosse County Clerk of Circuit Court Pam Radtke wrote in an email to Wisconsin Watch that judges in the county “do NOT monitor court-ordered financial obligations — once the obligation is ordered, the clerk of courts works on collections.” She did note that in some other counties “it is the practice … for the judges to hold review hearings to monitor payment.”

Melissa Pingel, Winnebago County clerk of circuit court and president of the Wisconsin Clerks of Circuit Court Association, said judges don’t typically monitor defendants’ payments in her county — a neighbor of Outagamie County.

“We don’t do the failure to pay warrants, we don’t do driver’s license suspension … because the philosophy here is that that’s only harming (defendants) more,” she told Wisconsin Watch and WPR, noting that those additional sanctions for being unable to pay court-ordered financial obligations can create a “cycle” of entanglement in the criminal justice system.

‘Collateral consequences’ feared

Prolonged involvement and contact with the criminal justice system, especially for low-level, low-income offenders, can “create a cascading series of harmful criminal justice responses,” experts told Wisconsin Watch and WPR.

“It becomes potentially just a cycle that a person can’t get out of: poverty, more punishment, more poverty, more punishment, more poverty,” said Marquette University Law School professor Michael O’Hear.

Said Wayne Logan, a law professor at Florida State University who studied the impacts of court-ordered financial obligations on defendants: “When you’re … still under the yoke of the system, that creates the opportunity for getting in further trouble with the system.”

A December 2018 report from the Wisconsin Director of State Courts Office, which oversees and manages Wisconsin’s court system, offered a similar assessment and added that jailing people for failure to pay often costs taxpayers more than it brings in revenue.

“Overall, arresting and incarcerating someone for failure to pay is an ineffective mechanism for collecting court-related (financial obligations) and should be used sparingly,” the report stated.

To help avoid these concerns, a subcommittee of Wisconsin chief judges in June 2019 made a series of recommendations about jailing defendants for the nonpayment of court-ordered financial obligations. Among the committee’s recommendations were:

- Before ordering financial obligations, the court should determine whether a defendant can reasonably afford to pay, and consider “imposing community service as an alternative” to payment;

- Counties should utilize the State Debt Collection program to recoup past-due payments — which the committee determined “is an efficient and cost-effective” system; and

- Eliminate “jail as a consequence to failure to pay, or (limit) it to the most egregious circumstances.”

Punitive responses to failure to pay are “not particularly effective, cost money and risk violating a defendant’s Constitutional rights,” the committee concluded, adding that financial obligations should be reduced to civil judgments and referred to the state debt collection service.

Shifting demands, failure to pay

In the case where Biskupic held 11 review hearings, the woman ordered to pay restitution was granted at least one extension on making the payments, court records show, while the judge continued to amp up the pressure. In June 2016, Biskupic ordered her to apply to at least 20 jobs over a two-week period — nearly 18 months after she was originally sentenced.

Court records also show that throughout the ongoing hearings, the defendant struggled with multiple physical ailments, including arthritis, pneumonia, broken ribs and a broken hand, which she said made it difficult to work. At one point, she was also temporarily unemployed “due to a plant close down,” court records show.

All the while, Biskupic continued to call her into court. But Flaherty, Biskupic’s attorney, said that was in part due to the defendant’s request for an extension to pay.

“(The defendant) and her attorney have never contested the court’s sentence,” Flaherty noted. “The prosecutor’s office has never appealed the court’s sentence. At several of the review hearings, (the defendant) asked for more time to make payments. The Court accommodated the defendant’s requests.”

Eventually, in December 2018, the court issued a civil judgment, ending any threat of arrest for failure to pay or appear at hearings. Only then, the defendant was back in Outagamie County Jail serving time. And as of July, she was back in jail for several crimes, including aggravated battery of an elderly person and possession of drug paraphernalia.

Phoebe Petrovic is a Report for America corps member. This piece was produced for the NEW News Lab, a local news collaboration in Northeast Wisconsin. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, Wisconsin PBS, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.