Back Home by Chris Hardie

» Download this column as a Word document

» Download the photos that accompany this story

» Chris Hardie’s headshot

Photos from the aftermath of a recent massive storm that flattened cornfields across Iowa and into Illinois and Indiana took me back 22 years.

The Aug. 10 storm damaged grain bins as straight-line winds of as much as 100 miles per hour cut a swath through farm country. The storm impacted about 38 million acres of farmland — including 14 million acres in Iowa, according to the Iowa Soybean Association. An estimated 8.18 million acres of corn and 5.64 million acres of soybeans in Iowa were affected.

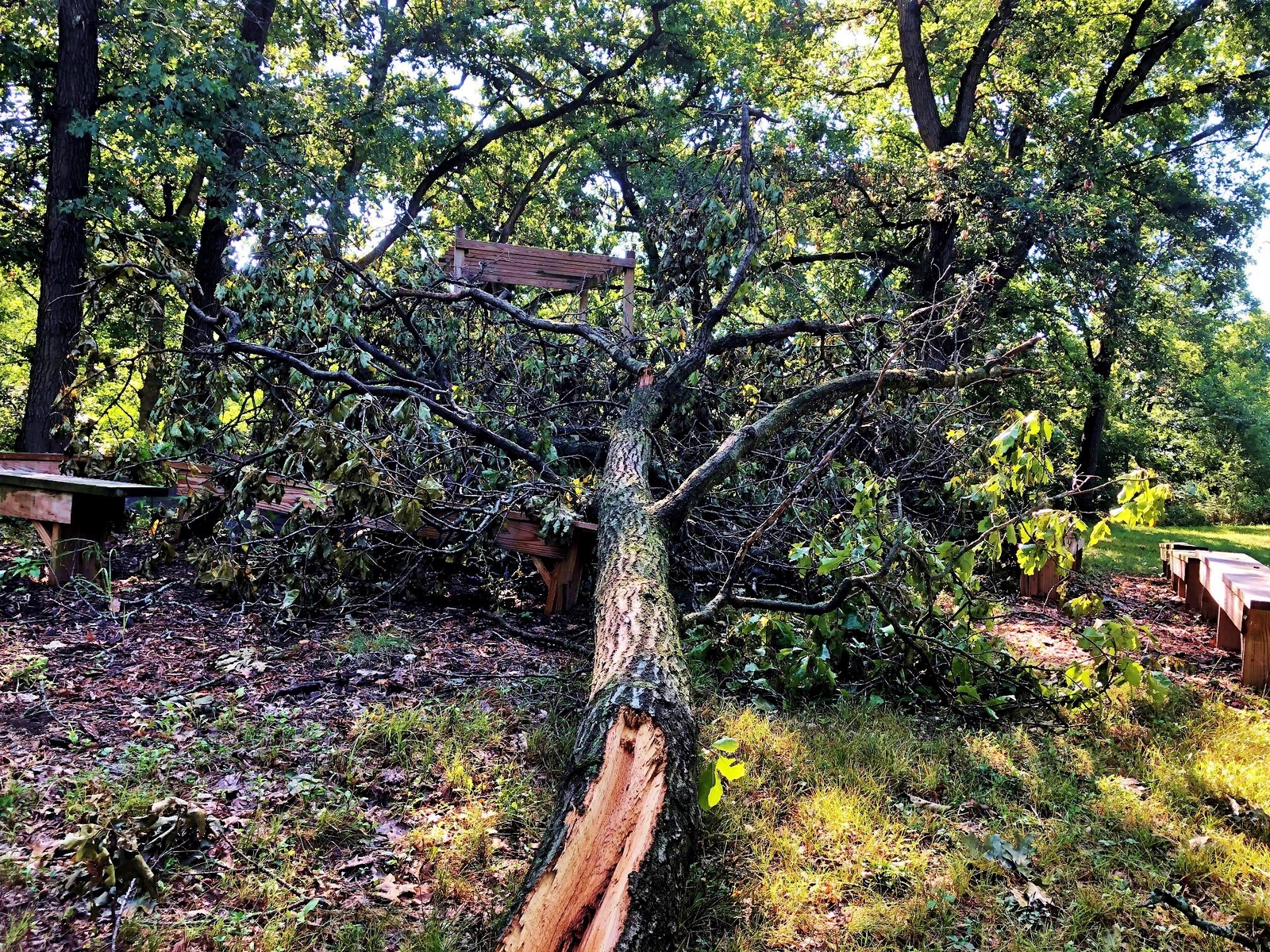

That same morning a slightly less-severe storm hit our farm. One tree limb smashed a few of our benches at one of our outdoor wedding sites, narrowly missing an arbor. A few other trees were toppled as was some of our patio furniture. Six plastic lawn chairs were smashed after the wind carried them several-hundred yards.

The derecho that ripped across Iowa reminded me of June 27, 1998, when a line of intense thunderstorms swept in from Minnesota and caused widespread straight-line wind damage to many areas of central and western Wisconsin. The National Weather Service called it one of the worst storms to hit the region in more than 25 years.

There were two main paths of the 1998 storm where winds gusted between 90 and 120 miles per hour. Our farm was on the northern track. I lived in West Salem near La Crosse at the time, but my parents were still milking cows. I was city editor of the La Crosse Tribune and spent that Saturday night on the phone helping to direct our news coverage while keeping an eye on the radar.

The storm took down big maple trees in my parents’ yard but they miraculously missed the house. One of them came straight down on their wellhead, knocking out their water. The power was out for several days. The milking equipment was powered by a generator, which my dad hooked up to a tractor.

The second house on the farm, where we now live, also escaped damage but with trees down. A large pine tree just brushed the side of the house.

My parents fared better than others. Several buildings, chicken-storage facilities and grain bins were leveled in Trempealeau County. I drove to the farm the next day to help with the cleanup and was astounded at the widespread swath of the storm, which flattened trees between Melrose and Cataract.

The storm came after a month of heavy rain and flooding. Trees were more vulnerable in the loosened soil. Many believed it was a tornado but the damage was caused by straight-line winds. The National Weather Service said wind gusts of 101 miles per hour were recorded in the Melrose area before equipment failed.

The southern track crossed the Mississippi River near the La Crosse-Vernon county line. Barns were destroyed; trees and power lines were blown down. In the Vernon County community of Christiana, one farmer was injured and his cattle needed to be rescued by firefighters after his barn collapsed.

Ten counties in western Wisconsin were declared a federal disaster area with more than $5 million in damages. Six southeastern Minnesota counties also were declared disaster areas; there was more than $8 million in damages in Mower County.

Dad and I cut trees all day with chainsaws. The well was repaired. There was some minor damage to the silo roofs but after the power was restored the farm was back in business. There was not significant damage to the crops.

The long-term impact of the storm was how the woods and landscape were changed by the number of trees blown over. But 22 years later, trees have regrown and there is little evidence of how destructive the storm was.

For farmers in Iowa, damage from the recent storm will depend on whether the corn was broken off or just bent over. Any corn snapped off will need to be harvested for corn silage. The impact on individual farmers will depend on the state of their crop insurance; damage to bins and elevators will affect storage this fall.

Either way, it’s a blow farmers didn’t need as we continue to cope in the strange and crazy year of 2020.

Chris Hardie spent more than 30 years as a reporter, editor