Back Home by Chris Hardie

» Download this column as a Word document

» Download photos that accompany this story

» Chris Hardie’s headshot

It’s a beautiful July morning as the sun climbs over the hill to shine on our valley.

Puffy white clouds dot the powder-blue sky.

The air is filled with bird songs.

It’s been a week since I watched my father, Robert Hardie, take his last breath. I selfishly tried to keep him with us a little longer but my life-saving attempts fell short. Dad died at about 7:20 p.m. on Independence Day, in his home with Mom at his side and his favorite drink in his hand — a tequila gimlet.

Dad, 82, had been ailing for several years after a bout with leukemia, reduced blood-platelet production that weakened him and dementia. His mobility had become limited. He fought the good fight.

We knew Dad’s time was growing shorter, so we had time to prepare. It’s easy to say but a little more difficult to do. Whether death comes suddenly or slowly, it’s still a shock.

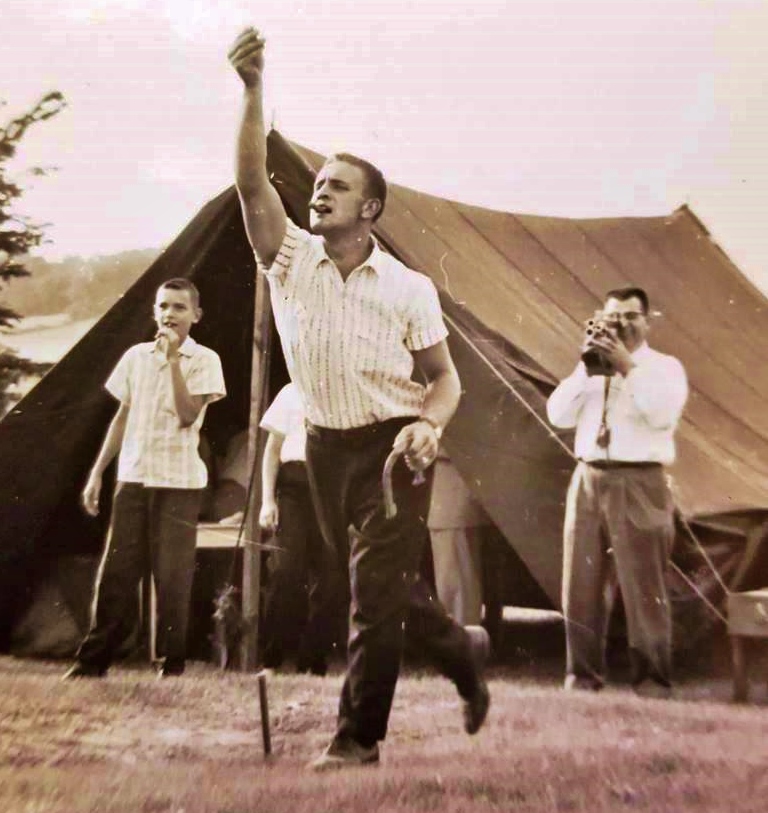

This past week I posted a photo on social media that was taken in 1956 at a family wedding reception. It showed my larger-than-life father as a 19-year-old pitching horseshoes with a perfect form and a cigar clenched between his teeth.

Dad was solid — 5-foot-10, 220 pounds — and anchored by a pair of size 13 EEE feet. He built his strength working summers as a teen on his uncle’s farm. Combined with a booming voice, he was an intimidating presence.

The photo generated lots of comments about my handsome father — taken three years before he was married and seven years before I was more than a glint in his eye. The celebrity comparisons were James Dean and Paul Newman.

Newman won out because that’s whom Mom thinks he looked like.

That strength likely kept Dad battling far longer than others would. Mom wanted him to see their 60th wedding anniversary; he did that plus 10 months. He was able to go into the woods this past fall for his 70th season of deer hunting.

In his final week, Dad spent time with his two sons, his five grandchildren and his seven great-grandchildren. It wasn’t a deathbed vigil, just a random series of visits. For a few brief hours at a family dinner, the fog of his dementia lifted enough that he told a few stories and laughed with the others — just like the good old days.

What a skeptic would call coincidence I would call divine providence. The family was drawn to Dad because it was time.

Dad’s voice was the topic of many family stories and was also featured in his funeral sermon. When Dad read liturgy in church there was no need for amplification. Little children sometimes asked if that was God’s voice. It also carried through the valley around the farm — whether we were being admonished or being summoned for a meal.

The gruff and tough persona mellowed in his later years. When my mother miraculously survived a major brain hemorrhage in 2007, he stayed at her side in the hospital for more than a month, coming home from Rochester, Minn., only once during the entire ordeal.

Dad became a better husband because he knew what he almost lost. And his soft spot for his grandchildren and great-grandchildren grew larger with each passing day.

In the end, Dad’s legendary strength and his booming voice were largely gone. But not his faith. This past fall as Dad sat on the porch during a pastoral visit, he was asked how he was doing.

“I’m ready to go,” Dad said, adding he didn’t know why he was still around.

Dad knew he was going the last time he looked at me, tears pouring down his face. My tears of sadness mixed with his tears of joy as I tried to breathe life into his mouth. But Dad’s last taste of dinner and tequila were no match for the sweetness of heaven.

They say people go through various stages of grief following the loss of a loved one — denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. But not everyone goes through all those emotions and they aren’t always in that order.

I’ve skipped through the first four because it was Dad’s time to go. It’s foolish and selfish to think otherwise.

And I take comfort in the words written by my grandmother Cecile Hardie in 1977, describing how she responded to the death of her mother the day before her wedding. Little did I know when I wrote about her story recently that her words would provide solace after another death.

“We have always known that after the rains, the sunshine comes because we know from our experience that sorrow doesn’t stay with you unless you dwell on it,” she wrote. “Happiness comes after grief.”

I am working on acceptance. Thank you for allowing me to share.

It grows better with each day.

Chris Hardie spent more than 30 years as a reporter, editor